For those with a shared allegiance to the University of Miami, the entire premise of Catholics vs. Convicts had to be met with a mixed bag of skepticism, general curiosity and a longing for an impartial take on an era-defining football game with a controversial ending.

ESPN’s 30 For 30 series has become synonymous with the Miami Hurricanes, courtesy of a two revered documentaries spanning the rise, fall and comeback of the storied football program on- and off-the-field over the past three-plus decades. When teasers began dropping regarding the Canes and Irish and that iconic 1988 battle in South Bend, it begged the question—who was behind this?

Miami faithful were understandably hoping it was Billy Corben and the Rakontur crew tied to the project; makers of “The U” (2009) and “The U Part 2” (2014)—two of the most popular vignettes in the acclaimed series. Instead, the name Patrick Creadon surfaced, prefaced by three words that immediately evoked unshakable feelings of bias—”Notre Dame alum”.

For the Canes enthusiast, optimism and excitement immediately shifted to expectations of elitism, embellishment and the type of trumped-up, fairy tale-type mystique, a la Rudy, where legend replaced fact.

Corben and his team produced two films that showed the good, bad and ugly of the Miami football program over the years—as well as unapologetically showcasing the city’s dangerous culture and climate at the time of the Canes’ initial rise to the top. The result was some universally-appealing storytelling which is why the Canes-themed docs always top any “best of” series list.

For fans of the Canes, Corben and crew’s films got the juices flowing as the best of yesterday was back on display. The epic victories, stockpiled championships and colorful personalities that helped transform a small, private school in Coral Gables into a national sensation.

Regarding the anti-U crowd; enough footage of heartbreaking losses, titles left on the field, the NCAA gutting the program—twice—and distressing moments for an opposing viewer to gleefully celebrate a villain’s demise.

Catholics vs. Convicts proved to be the exact opposite. Like a kid with a face so ugly, only a mother could love—this Fighting Irish stroke-fest oozed with schmaltz and holier-than-thou sentiments at every turn.

For the contingent who deem South Bend sacred, a carefully-crafted love letter for a fanbase over two decades removed from championship glory. For literally everyone else, an all-too-familiar feeling regarding an Irish slant and beer-goggled storytelling.

SHAMROCK-COLORED GLASSES ON DISPLAY EARLY

First-person plural from the get-go, Creadon uses “we” when talking about Notre Dame football and history—immediately setting the tone that “fair and unbiased” are going right out the window.

This trip down memory lane is being told by a Golden Domer with Irish blood pumping through his veins. Casual viewer, be damned—Creadon’s revisionist history was aimed directly at those who experienced this era of Notre Dame football from a shared super-fan vantage point.

The Creadon family’s deep ties to South Bend were on display heavily in the film’s first act. Dad graduated from Notre Dame; his love for the program rooted in the Irish doing it “with class and dignity”, while Gramps was recruited by Knute Rockne. An impressive legacy, sure—albeit told with a smug and familiar we’re-better-than-you sub-plot that had nothing to do with the bigger story.

Early on, it’s explained that outside of revisiting the game, a portion of the film was dedicated to figuring out why the moniker “Catholics vs. Convicts” stuck. Why did some feel it was “funny and accurate”, while others—Creadon included—thought it was “mean-spirited and reckless”?

That question really never gets answered from the filmmaker’s perspective—though Miami-bred columnist Dan LeBatard spelled it out in a way that sums up precisely why the Canes got under that soft, Irish skin.

“They’d tell you there were gonna kick your ass. They’d kick your ass and then they’d celebrate the kicking of your ass.”

Damn straight. Spoken like a unique and authentic Miamian who survived the Magic City during that era.

For an upper crust program like Notre Dame that dominated in the leather helmet era—the brash inner city nature of the ultimate anti-establishment program taking you behind the woodshed—that was never going to sit well and proved to be the tipping point in this story.

Barely two minutes in, Creadon is speaking with college buddy and one-time t-shirt mogul Pat Walsh about the design and the screen goes black, followed by the phrase, “Three Years Earlier” and the notorious date—November 26th, 1985. Everything officially clicked and Creadon was off the races, building his entire “convicts” argument on the historic 58-7 walloping the Canes dropped on the Irish that fateful South Florida evening.

BRASH & DOMINANT CANES SCAPEGOAT FOR FAUST’S INCOMPETENCE

All credibility was initially out the window when a biased Domer zeroed in one game in this storied rivalry—ending on a controversial call, no less—earning the Irish their lone championship dating back to 1977. Crying foul over the 1985 showdown—where Miami’s third string was creating turnovers and finding the end zone—laughable, considering Notre Dame’s reputation for beating the Sisters Of The Poor, 147-0 in their hey day.

False pride and bruised egos led to this manufactured subplot regarding any “disrespect” shown to dead-man-walking, Gerry Faust—who resigned a few days prior.

The beloved head coach was 5-5 headed into the season finale—leaving him a dismal 30-25-1 late in his fifth season. A revered high school coach for two decades, the inexperienced Faust was thrust onto a main stage that proved too big. Even after a spending nine seasons under the radar at Akron, Faust’s collegiate career ended with a 73-79-4 overall record—canned after a 1-10 season in 1994.

Quoting villainous gang-boss Marsellus Wallace, “Pride only hurts, it never helps”. Wallace’s words were intended as solace, as he encouraged “punchy” Butch Coolidge to throw a fight, in the 1994 neo-noir black comedy crime film Pulp Fiction.

On the evening of a 51-point beatdown, Notre Dame’s pride was certainly “f**king with” them—followed by a long plane ride home to stew regarding their then-level of insignificance, which ultimately sparked the sour grapes. Even in a documentary intended to highlight a perfect season and rare modern day national championship in South Bend—the Irish couldn’t let go of what happened three years prior, still visibly rattled by those four quarters in 1985.

WNDU anchor Jack Nolan ranted and raved that Faust’s last stand at Miami should’ve been “quiet and respectful” and “like a state funeral”—as if a Hurricanes team dominated by the Irish years prior somehow owed a sub-par rival coach some type of reverence? Nolan even goes as far as to compare the Fighting Irish to a baby deer that the Hurricanes ran over, stopped and backed up to hit again—an absolute joke of an analogy to anyone outside of South Bend who watched the University of Notre Dame play the role of bully for decades before more parity, diversity and speed entered the game, eventually leveling things out.

The displaced frustration pathetic, laughable and deserves to be called out.

Fast-forward thirty years and Miami was on the wrong end of a 58-0 ass-kicking, courtesy of Clemson in 2015. Up 42-0 at the half, the Tigers scored two fourth quarter touchdowns en route to delivering the worst beating in Canes’ football history. Similar leadership narrative, too—a maligned, decent-guy head coach in his fifth year who wasn’t getting the job done.

When those four quarters were over, did Miami bitch, moan and complain about Clemson piling on? Fat chance. Hell, most disgruntled fans were thankful to Dabo Swinney and the Tigers for putting the final nail in the coffin that was the Al Golden era. The guy with the tie was canned the next morning, having spent the previous couple of years cleaning up an NCAA mess he didn’t deserve to inherit.

Golden wasn’t much of a leader, but at least he wasn’t a quitter. Faust waiving the white flag for a program once known for the grit and toughness of The Four Horsemen—no way that sat well in South Bend, which seems to have led to the misappropriated anger.

The revisionist history and manufactured storyline surrounding Faust was nothing more than a way to take the focus off the fact the “Fighting” Irish had simply become plain ol’ Notre Dame—something former Miami defensive end Bill Hawkins touched on in a quick soundbite, boastfully explaining how the Domers were mere mortals who lost all their fight. “Unbeatable” author Jerry Barca took it a step further when he got some screen time.

“In the Faust era, players voted to have shorter practices. They had to take three votes to go to a bowl game, because twice it got voted down. College kids not wanting to play another football game. It was bad,” expressed Barca, still baffled as to the program’s soft ways under Faust.

That denial and deflection, coupled with expected elitism, a sentiment that NBC’s Chuck Todd—a Miami native and Canes’ supporter—summed up with one perfect sentence. “It was sort of like, ‘Wait a minute—how dare Miami throttle Notre Dame in the way that Notre Dame used to throttle other people,'” mocked the antagonistic political analyst.

JJ WORRIED ABOUT OWN LEGACY; NOT THE IRISH’S UNRAVELING

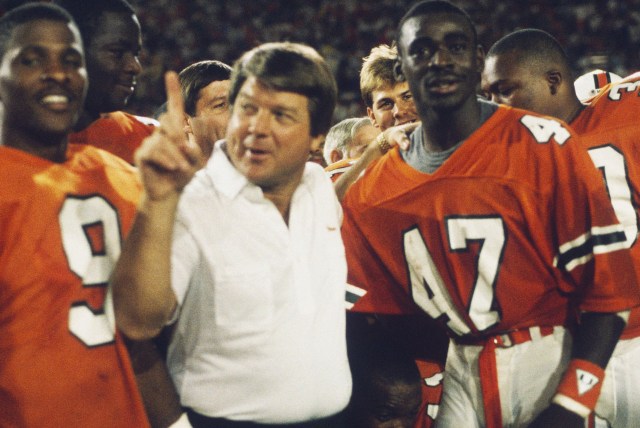

The final missing piece—something Notre Dame faithful choose to eliminate from their version of history; complete disregard for Miami trying to work its way back into the national championship picture under second-year head coach Jimmy Johnson. The Canes opened the 1985 campaign with a loss to fifth-ranked Florida, before rattling off a nine-game win-streak, boosted by road upsets of No. 3 Oklahoma and No. 10 Florida State.

Also lost in the shuffle; the fact that Johnson replaced Howard Schnellenberger in 1984—a legend and pioneer who came off like a pipe-smoking prophet when he delivered the national title he predicted by 1983, in what proved to be his fifth and final season in Coral Gables. Months later, Johnson got off to a respectable start with the defending champs—taking down Auburn and Florida—but Miami was soon 3-2 after losses to Michigan and Florida State, inviting criticism from a newly-spoiled fan base.

Johnson’s Canes ratted off five wins in a row—including a 31-13 victory in South Bend—before a nightmarish three-game skid to end the season 8-5.

Incomprehensibly, Miami blew a 31-o halftime lead in a 42-40 loss to Maryland, followed by Thanksgiving weekend’s “Hail Flutie” miracle against Boston College and coming out on the wrong end of a Fiesta Bowl shootout against UCLA. Months later, the aforementioned season-opening loss at home to the hated Gators—the Canes’ last Orange Bowl defeat before tearing off 58-straight victories over the next ten years.

Putting it in the simplest of terms; Johnson and the Miami program had more-pressing concerns than Faust’s resignation or suggested “state funeral” show of respect. Johnson and his Canes looked to sway voters, en route to a title shot—and a convincing national stage win, over a one-time powerhouse—could go a long way when bowl games were selected.

Even with this logical, football-driven reasoning—emotionally-fueled bitterness remained—leading to Creadon’s focus on Notre Dame exacting revenge two months, later on the hardwood.

Former Notre Dame basketball coach Digger Phelps—in self-congratulatory fashion—blethered about the beat down they laid on a Miami program that had been dormant for 14 seasons and resurrected months earlier. Phelps was proud to have piled on, his boys winning by 53 points —“Two more points than football lost!”—waxing nostalgic regarding his squad’s return to South Bend; football players waiting at the airport to welcome and thank them.

The Phelps’ anecdote, nothing more than Creadon case-building to justify Notre Dame’s referring to Miami as “convicts” on a t-shirt—with zero awareness in regards to Irish hypocrisy. In the Golden Domers’ economy, an eye-for-an-eye tactic replaced turning-the-other-cheek—where gridiron embarrassment was paid back by way of shaming the equivalent of a upstart basketball program, a few games into their first action since 1971.

A vintage-era, Notre Dame approach to bullying the little guy—just like they did for decades—and being completely all right with it. Creadon should guest lecture a course called, Flawed Irish Logic: 101.

As Catholics vs. Convicts continues to unfold, the Miami hatred continues to unravel—jealousy tones, scowls and smugly delivered soundbites sprinkled throughout.

“If you don’t want people to be upset, show a little class,” whined local radio anchor Nolan—a fool to believe the Canes actually gave a shit what the critics thought—while former offensive lineman Tim Ryan could barely keep a lid on his envy and programmed elitism.

“Those guys went down to Miami Beach and had access to all kinds of stuff. We had a little bit of a different approach. Notre Dame goes above and beyond in trying to do thing the right way and takes this very seriously.”

With more time, one could unpack how “access” to all the spoils of Ocean Drive counters doing things “the right way”. As for taking things very seriously, Miami played for seven championships between 1983 and 1992—winning four, while deprived of a title shot in 1988.

It’s strange to infer that mighty Notre Dame would have any inferiority complex in regards to then-upstart Miami—but for whatever reason, the Cane-envy is palpable throughout. Former UM offensive lineman Leon Searcy made what was probably a throwaway statement to the film’s editors regarding the 1985 game being that moment where the Irish finally saw things for what they had become.

“I think that’s when Notre Dame finally considered us a rival.”

BIG BROTHER COULDN’T STOMACH LITTLE BROTHER RISING UP

A quick history lesson regarding these opponents ultimately became foes.

Miami and Notre Dame first went at it in 1955; the Irish winning, 14-0. The Canes bounced back with a 28-12 victory in 1960, when the two met again. In 1965, a 0-0 tie, leaving both sides were 1-1-1. From there, Notre Dame rose up and tore off an 11-game win-streak between 1967 and 1980—the most-lopsided victory coming in 1973; a 44-0 shellacking at the Orange Bowl.

The Canes finally broke that streak in 1981 with a 37-15 pasting—Schnellenberger going on to lead Miami to a 9-2 season that also included a homecoming win over top-ranked Penn State. Little brother was all grown up and the once-ridiculed Sun Tan U was morphing into a program that would soon dominate and instill fear.

The Canes went 6-2 against the Irish in the 1980’s—including a four-game win-streak going into the 1988 battle highlighted in this documentary—while wins in 1983, 1987 and 1989 helping spring Miami to national championships. If you’re self-anointed big, bad Notre Dame—that’s a bitter pill to swallow, no matter how you try and package it or prop up the “Catholics vs. Convicts” showdown and the role it played in the Irish’s most-historic season.

Sifting through all the mushiness and seeing things for what they are—outsiders will realize this is nothing more than a well-crafted propaganda piece.

The dewy-eyed segment on the stand-up Tony Rice that played out in fairy tale-fashion—solely due to his on-field success and place in Irish history—began with excerpts from the student newspaper where elitism was on full display; fans calling Rice, “intellectually inferior”, “ridiculously unqualified”, while verbalizing that he didn’t belong in South Bend and his acceptance to the university was seen as “lowering our standards” and would “jeopardize our reputation”.

The father of one young fan even told his son, upon meeting his hero, to not grow up to be a “dummy” like Rice—rattling the quarterback to the point he called his family and expressed a desire to leave the program.

Fittingly, none of that mattered once the wins started piling up and the Miami dragon was slayed. Rice instantly became a folk hero. Same to be said for the irony in Irish faithful referring to the Canes as hoodlums, while the documentary romanticizes Walsh’s bootleg t-shirt business and his entrepreneurial-type spirit.

DOUBLE STANDARD APPROACH TO FLAWED DYNAMICS ON BOTH SIDES

The storytelling essentially justifies all copyright infringement with an explanation that collegiate licensing at the time wasn’t what it is now, while driving home shirt mogul Walsh’s present-day remorse—which seems to stem more from getting busted and dismissed from Notre Dame’s basketball program than any real regret for illegal activity.

The premise for “Catholics vs. Convicts” was birthed out of two Miami players arrested prior to the 1988 season—a reserve defensive tackle who sold drugs to an undercover cop and another who stole a car with a friend.

Both are crimes absolutely deserving of punishment—but much like sin itself, who is man to deem one transgression more erroneous than another? Is selling illegal drugs “worse” than selling bootleg t-shirts? Both were done by college kids seeking supplemental income. One just happened to be black and from Miami’s inner city, while the other was a white, from the Midwest and attended a university with a sterling reputation.

By the standards of Catholics vs. Convicts, one is led to believe that slanging Hanes Beefy T’s on campus is slap-on-the-wrist worthy—with Creadon’s film working to build sympathy for “Walshy”; constantly hammering home his life’s goal of playing basketball for the Irish and that dream taken away.

While there’s much to be critical of regarding Creadon’s sentimental set-ups, the game-related portion of the film came off unbiased—until the cartoon character that is Lou Holtz surfaced.

Everyone else involved—especially on the Irish side—dropped their schtick in favor of a reverence for what took place on the field that day. Notre Dame players came off less defensive and bitter, while Miami’s athletes—even in defeat—hold that contest in high regard. Everyone involved that day knew they were a part of something special.

Regarding the coaches, Johnson was transported right back to the moment, not wanting to watch footage of the phantom Cleveland Gary fumble and blown call that mistakenly gave the Irish possession in the shadow of their end zone—while the forever sanctimonious Holtz claimed that he’d never seen footage of the Andre Brown touchdown 28 years later.

For pure theater; a Holtzism about that referee not getting his way into heaven for calling that Hurricanes grab a touchdown. (For the record, both officials in the end zone signaled the score—which it was regarding the catch rule in that era, which has since changed.)

CBS Sports’ Brent Musberger, who called the game and in typical, stuffy commentator fashion—still snickered about the controversial tee, praised the educational rehabilitation of quarterback Rice and refused to give an inch on the position he’s held for years—be in the 1985 game, the Gary “fumble” or the villainous label slapped on Miami; never even once playing devil’s advocate.

In case all of that wasn’t enough for Canes Nation to boil over; Creadon saves his ultimate weak-sauce dig for last—an insinuation that Miami’s pounding of Notre Dame in November 1989 was the result of a tight and watered-down Irish bunch, afraid of Holtz’s supposed threat to yank scholarships if his players engaged in any pre- or post-game fisticuffs. Without said clamp-down, a pointless “what if” moment.

Miami tipped its hat to Notre Dame; Johnson admitting on camera they were the better team that day in 1988. When presented a comparable moment regarding the 27-10 takedown of the defending champs and nation’s top-ranked team sporting a 23-game win-streak—Creadon instead chose a caveat and self-imposed an asterisk on a game that didn’t need one; the Canes proving who they are, while the Irish showed their asses, yet again.

May the filmmaker remain tortured by that loss just as team captain and Irish linebacker Ned Bolcar were when interviewed on hallowed Orange Bowl grounds in the wake of defeat.

“This one is going to haunt us the rest of our lives. I hate this damn place.”

Agreed. Just as a viewing of Catholics vs. Convicts and that controversial afternoon in South Bend will forever haunt Canes enthusiasts, elitist Domers.